The woman looked at me with a stunned expression. She looked as if she had suddenly witnessed an elephant disappear in front of her eyes.

“How did you do that,” she asked.

It was a clinic and the woman brought a horse that danced around like a balloon in a windstorm. She was trying to lunge her horse on a small circle, but it had other ideas. Nothing she did convinced her horse that circling quietly around the owner was a good idea. She twirled the rope to tell him to circle, then she bumped the rope to stop him from fleeing, then she pulled on the rope to prevent him from pulling backward. Everything the woman did seem to just exacerbate the horse’s anxiety.

After a few minutes of watching and encouraging the woman to try different approaches, I asked if I could take the lead rope. She seemed very glad to pass the problem to somebody else.

The first thing I did was to try to rub the horse on the face. I wanted to introduce myself and say “hi.” It did its best to avoid my touch, but I used one hand, then the other to centre the horse’s thoughts directly at me. When I could make contact without the horse attempting to evade me I felt the hardness and stiffness in the muscles of the neck. It was like I was rubbing the end of a plank.

I placed the palm of my hand on the bridge of the nose with my thumb on one side and fingers on the other. I gently pushed my hand towards the horse and felt no give. The horse’s head did not move one iota as if it was made of granite. I pushed again and again with just enough pressure for the horse to be confused. For some time the feel of a dead plank persisted as I kept gently pushing. Then I felt a small give at the poll. The poll flexed just a fraction and the head tilted in and bounced back out. I repeated it and felt another give. Another try and another. With each push of my hand, the head of the horse started to softly bounce in and back out, as if I was compressing a soft sponge and releasing it again.

When I was certain the resistance to my hand had fallen from 100 percent to maybe 10 percent, I asked the horse to lunge in a small circle around me. Suddenly the horse was behaving like the sweet well-educated horse the owner always wanted. The circles were real circles and the horse was calm and quiet. The owner looked amazed.

Nobody at the clinic was clear about how bouncing a horse’s head could teach a horse to lunge beautifully.

This story gets repeated in some form or another at least once at virtually every clinic I teach. By that I mean I address a problem by taking a very roundabout route instead of head-on. It’s hardly ever by bouncing a horse’s head, but sometimes it is. Maybe I will work on moving a foot in a very specific way or maybe I will ask for the horse not to lean on the lead rope or maybe I will work on getting a horse to hold a gaze. The list of things I might ask of a horse to change to address an issue indirectly is too many to list. And they don’t matter.

They don’t matter because the exercise itself is irrelevant. Helping that horse lunge better could just as easily have occurred by asking it to allow me to softly pick up its tail instead of bouncing its head in my hand. The problem was not the lunging in small circles or the inability to bounce the horse’s head; the problem was the horse’s emotions.

The session began with the horse in emotional turmoil. The turmoil hindered the horse’s ability to focus. It was trying to save its life. But the owner kept getting in the way of the horse’s thought to save its life. This made things worse. It was only by asking the horse to search for something – like giving to my hand by flexing at the poll – that I was able to find a way to change the emotions.

In essence, the emotional anxiety at the beginning determined the horse’s thoughts to run, pull away, call out, try going the other way, etc. It is only by changing the emotions that the horse was able to listen and follow a feel.

On the surface, many people would think they needed to work on the problem of lunging the horse. They would need to move the horse’s feet. They would circle and circle the horse until it demonstrated some semblance of a reasonable circle. It becomes about relying on the exercise and moving the feet to fix the problem. Even bouncing the head of the horse could be made into an exercise that did nothing towards helping. Moving the feet or doing exercises for the sake of doing something is just surface training. It’s not anything helpful in carrying forward the learning process.

A horse can only learn by changing its thoughts when asked a question. And thoughts can only change once a horse has let go of the thoughts it presently holds. It’s the emotions of a horse that determine how ready it is to let go or hold onto its thoughts. Only soft emotions enable a horse to easily learn the things we want in training.

I think the story in this post is just another example that good horsemanship is always about influencing a horse’s emotions and thoughts to direct the feet and not the other way around as I so often hear.

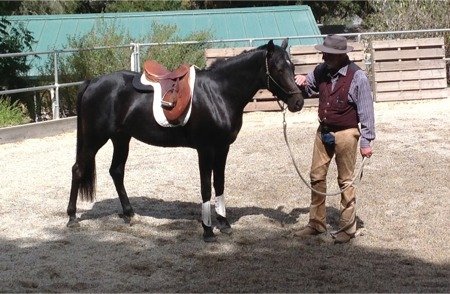

At a clinic in California I am attempting to get a horse’s thoughts in my hand.